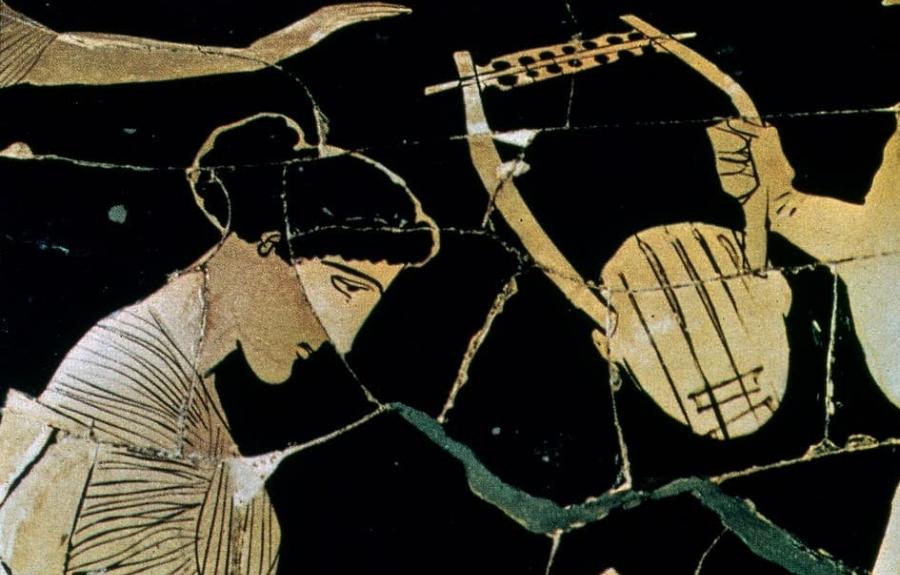

[n.d.]. Hydria: Sappho: det.. Place: Ethnikon Archaiologikon Mouseion (Greece). https://library.artstor.org/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003050760.

Lyric poetry has always been a media problem. Despite its long dependence on the written page, there are few more enduring commonplaces in literary history than lyric’s so-called “musicality”—the prosodic, ideological, and historical claims to sound that render silent texts so variously audible. Either as the putative transcriptions of past speech acts, or scripts for future ones, lyric poems resist and unsettle their print medium by bringing the silent page into contact with other media, not least the speaking and listening body. The word lyric itself alludes to a musical technology—the ancient Greek lyre—though lyrics have had relatively little to do with actual instruments since Alexandrian scholars inaugurated a written lyric tradition in the second century B.C. This presentation will propose reactivating the lyre in lyric as one theoretical strategy for apprehending the long history of lyric media, and for grasping lyric itself as an exemplary media problem, one defined by the historically variable, phenomenally mercurial tension between writing and sound.

Insisting upon the lyric’s lyre invites us to acknowledge in what sense the lyre persists, as a constitutive absence, throughout the history of Western poetry. Of course this instrument and its look-alikes, the lute and harp, are ubiquitously present on the printed pages of the literary tradition, whereas trope, theme, or character they signify poetry’s ideological proximity to music and remark its prosodic ambitions. And of course various actual lyres have been significant actors in literary history, from Thomas Campion’s lute to the psaltery of W.B. Yeats, reminding us of poetry’s material relations with song forms and with musical practice. But the fact remains that on the written or printed page, the lyric poem is always materially missing its lyre. Its constitutive absence indexes the tension between text and sound at the very heart of lyric practice, what we can term its intermedial condition. All alphabetic writing is minimally intermedial, to be sure, but the poetry we have consistently called lyric—and much poetry besides—represents that special kind of writing which takes intermediality as a motor of formal innovation and as a unique source of cultural appeal. The missing lyre signs and certifies this intermedial dynamic.

In the twentieth century, the absent lyre finds an uncanny counterpart in the presence of new technologies for the reproduction of sonorous speech and music. In the interest of more concretely establishing the stakes of a media-studies approach to lyric, this presentation will look briefly to one specific period and place—the 1930s U.S.—and one specific poem by the late modernist poet Lorine Niedecker (1903-1970), a devotee not of lyres but of the radio, “an instrument much more amazing than the lyre ever was.” As we will see, in addition to helping us account materially for the way lyric poems operate between sound and print, casting lyric as a media problem—as a practice missing its lyre—also reveals modern poetry as a remarkably sensitive indicator of the social history of sound technology.

Matt Kilbane is currently completing his Ph.D. at Cornell University where he works at the intersection of literary and media studies, with a special focus on twentieth-century American poetry and the relationship of literature to music. His article on the composer Harry Partch is forthcoming in PMLA.