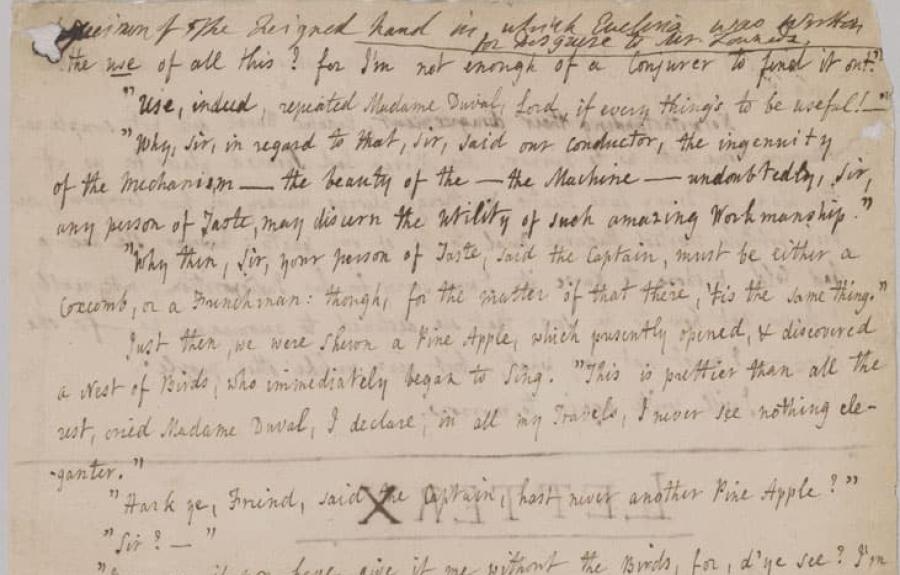

Autograph manuscript fragment of Evelina, written in a feigned hand. Collection of Fanny Burney Letters and Manuscripts (MA 35.1), The Morgan Library & Museum, New York.

This manuscript page is the sole surviving leaf of a fair copy manuscript of Frances Burney’s first novel Evelina, or A Young Lady’s Entrance into the World (1778). It is currently held at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City, whose holdings derive from the personal library and art collection of the American financier J. Pierpont Morgan. Morgan purchased the leaf from a London book dealer named Quaritch in July 1905 as part of a collection of Burney’s papers, although the rest of the Evelina manuscript is now lost.

Burney is mostly remembered today as a major novelist of the eighteenth century and precursor to Jane Austen, who took the title of her novel Pride and Prejudice (1813) from Burney’s novel Cecilia (1782). After her death in 1840, Burney left an extensive archive of manuscripts, journals, diaries, and a large trove of personal correspondence totaling more than a dozen published volumes. Yet this single page is unique in that it is written in a “feigned hand.” That is, Burney used a disguised handwriting to conceal the fact that she was writing the novel from her family. Her father, Dr. Burney, strongly disapproved of her writing fiction, which was considered inappropriate for a young lady of her social status. To escape Dr. Burney’s watchful eyes, Burney salvaged used papers from her household and often wrote in the attic of her house secretly at night, copying the novel’s more than 300-page manuscript in the feigned hand, after working for her father as secretary and copyist during the day. She also used the same feigned hand to correspond with potential publishers to solicit the novel’s publication. In January 1778, when Burney was twenty-six years old, Evelina was published anonymously by London bookseller Thomas Lowndes without her father’s knowledge or permission. The publication of the novel was Burney’s own entrance into the world of professional authorship and public life, and by the year’s end the novel was a runaway critical and commercial success.

Reconceptualized as media object, this artifact enables literary studies to think more broadly and fluidly within and across media forms, reaching beyond traditional taxonomies of textuality, genre, and literary tropes towards non-discursive means of representation. In particular, the special materiality of the feigned hand challenges the primacy of written, discursive text as the basis of the study of literature, as the feigned hand is able to communicate the challenges Burney faced without words at all. In more theoretical terms, the feigned hand is a non-discursive engagement with the materiality inherent in manuscript culture—the embodiments of pen, ink, and paper elided by mechanized print later in the century—that can produce meaning alongside more conventional, discursive, and textual representation. It is a distinctly human imprint and form of mediation forged against the forces of gendered violence in a publishing environment and reading public dominated by unrelenting male critics; this mode of producing meaning is therefore directly gendered, registering not only social pressures working against women and patriarchal attempts at discursive control but also the empowering effects of female literacy and accompanying resilience. It affords women’s writing a quasi-agential resistance to the silencing, erasure, and discrediting practiced against female authors, amidst tectonic shifts in dominant media forms not unlike those in the present day.

Pichaya Damrongpiwat is currently completing her Ph.D. in English at Cornell, specializing in eighteenth-century studies, gender, and materialism. A portion of her dissertation, “Rape, Female Literacy, and Fictions of Materiality in the Eighteenth-Century Novel,” is forthcoming at The Eighteenth Century: Theory and Interpretation.